Tech War Tensions: China Restricts Graphite Exports

Chinese Graphite Mine Source: Evgeny_V/Shutterstock

On Friday, December 1, China began new export restrictions on the key rare earth mineral of graphite. The new restrictions will require state approval for high-grade graphite exports to foreign nations. The restrictions come just days after the U.S. government imposed new controls on artificial intelligence chips en route to China, prompting many to affix the two restrictions together and contextualize them within the broader U.S.-China technology competition. This notion of a weaponized Chinese export ban/restriction is beyond mere speculation; Chinese state media furnished a concurrence of the concept, exclaiming that “restrictions on critical minerals are payback for Washington’s efforts to curtail Chinese access to advanced American semiconductors.”

The U.S.-China tech war dates back to the Trump administration, but really came to fruition last year. In August of 2022, Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act to facilitate the withdrawal of semiconductor manufacturing abroad and expand the industry domestically for economic and national security reasons. This was followed by imposing export limits and restrictions on advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China in September of this year. The United States has also set restrictions on American citizens working in semiconductor-related industries within China, as well as a recent executive order which limits the ability of U.S. companies to invest in China’s semiconductor industry. As U.S. President Joe Biden stated last year, “semiconductors are small computers that power… smartphones, cars, the Internet, electric grid, and so much more, including our national security. We need semiconductors not only for… Javelin missiles, but also for the weapons systems of the future … This goes well beyond commercial need.” In response to U.S. measures, China restricted exports of gallium and germanium, two other rare earth minerals, to the U.S. back in July.

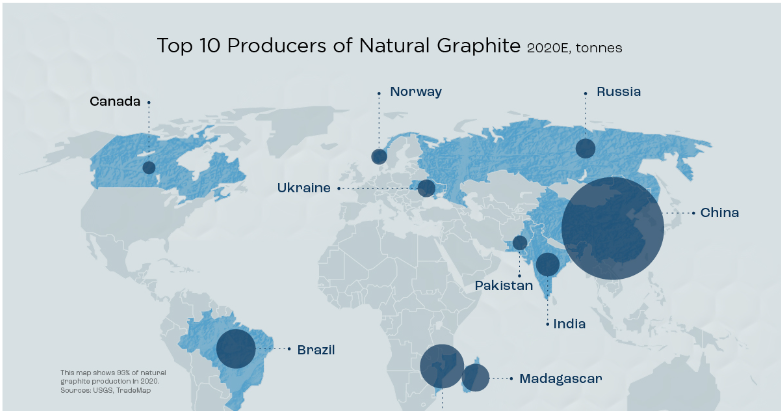

Chinese rare earth mineral export restrictions, like those on graphite, serve as especially potent weapons against the United States and its allies. China produces 98% of the world’s gallium, 60% of the world’s germanium, and nearly 66% of the world's graphite, all of which are crucial in the production of electric vehicles, semiconductors, and batteries. As the dawn of the green job era approaches the United States, its main adversary holds a virtual monopoly on the raw elements needed for its realization. In addition, the only U.S. allies with notable graphite production are Canada and Norway, with a scant 1.1% and 0.75% of the world’s production, respectively.

Worldwide Graphite production by nation Source: Elements by Visual Capitalist

China’s message to the United States is loud and clear, with Chinese officials even going so far as to categorize graphite as a “dual-use item that can be used in military or civil applications,” mocking similar arguments made by the U.S. government to support the semiconductor export bans to China. However, as strong as China’s position may seem to the United States, there are some caveats. It is true that China produces the majority of the world’s graphite and rare earth minerals. However, this is more due to economic efficiency than necessity. Chinese subsidies for rare earth mineral mining have allowed China to dominate the market, providing the world with cheap minerals. Many other nations have similar or even larger graphite reserves than China. One example is NATO-aligned Turkey, which has the largest graphite reserves in the world, but currently chooses not to capitalize on those reserves as they can import cheaper graphite from China. Nations like Turkey could theoretically ramp up graphite production if needed.

Additionally, new generations of technology such as electric vehicles are projected to be built without the use of rare earth minerals, rendering the future of China’s current mineral monopoly relatively lackluster.