Afghan Refugees in South Korea Resurface Past Controversy

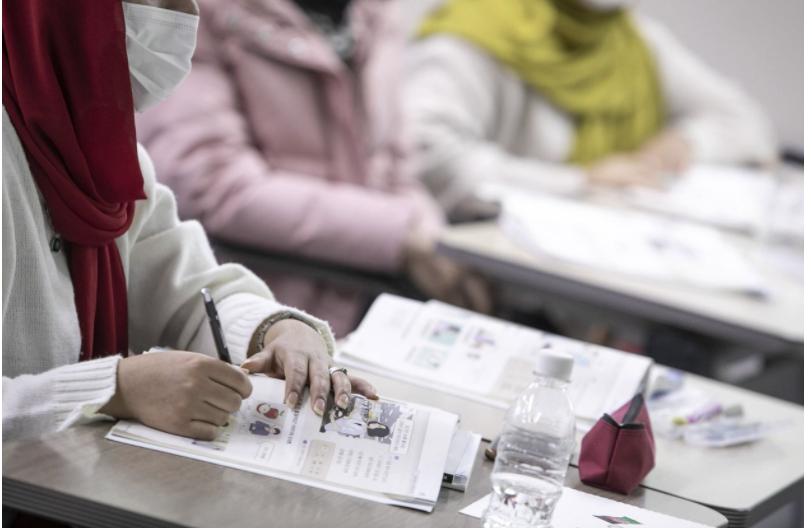

An Afghan woman participates in a Korean language session. Photo: Jean Chung / Washington Post

Since the Taliban seized power of Afghanistan in August of 2021, some Afghans have found asylum in an unlikely host country - South Korea. The fall of Kabul to Taliban forces prompted the South Korean government to accept nearly 400 Afghans in an effort labeled “Operation Miracle.” In a five-month program that concluded this February, Afghan refugees took part in lessons on culture, language, and economics in South Korea.

Now, they face the challenge of adapting to a society with an existing foreign population of just 5%. The arrival of a significant refugee population has reignited controversies surrounding South Korea’s anti-refugee sentiment.

The reluctance to grant Afghans refugee status, and instead the designation of “special contributors,” is reflective of the country’s adverse relation with the term itself. In June of 2018, the arrival of 500 Yemeni refugees sparked mass protests and a petition in favor of revoking their refugee status signed by over 700,000 people.

Much of the opposition was attributed to Islamophobic overtones and the use of the European refugee crisis as a warning of the consequences of accepting refugees. The term “fake refugees” became a popular slogan of the June 2018 protests. In response to mounting pressure the government refused to grant Yemenis official refugee status and instead they received a one-year residence permit.

Afghan refugees have received a drastically different welcome than the wave of Yemenis in 2018. Nearly all 80 families had worked at the South Korean embassy, Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), and a Korean-owned hospital. The F-2 visas granted will allow Afghans to work and reside in the country for up to five years, and applications will be made available at a later date for F-5 permanent residency visas.

Both liberal and conservative politicians have expressed support for the program, and President Moon Jae-in stated that it was “Only natural for us to fulfill our moral responsibility by helping the Afghans who helped our operations.” A survey conducted in South Korea indicates strong public support for the program as well, with 68.7 percent of respondents agreeing with the government’s plan to give Afghan contributors visas for prolonged stay and employment.

The government has seemed to avoid a similar controversy to 2018 by avoiding a refugee classification. Polls have revealed that survey results on public support are higher when the term “special contributors” is used in comparison to refugee. South Korea’s youth population is the demographic with the strongest opposition to accepting refugees, a trend that was also apparent in 2018 polls. This may be tied to widespread unemployment and disenfranchisement among youth in South Korea that have fostered a sense of animosity towards immigrants.

Afghan refugees arrive at Incheon International Airport in South Korea. Photo: Kim Hong-Ji / Washington Post

Afghan refugees will likely face additional challenges assimilating to life in South Korea, including culture shocks in language, work life, and population density. The lack of an established Afghan community, just 837 prior to the new influx, may increase the sense of isolation felt by many new immigrants in the country. Hostility towards foreigners is closely connected to the South Korean mantra of “danil minjok,” which alludes to a racially pure monoethnic nation. The country’s North Korean refugee population, standing at roughly 30,000, has not been confronted with the same obstacles as other minority groups when assimilating.

South Korea is now grappling once again with several questions regarding the acceptance of refugees. Its assimilation program for the Afghan arrivals has already drawn criticism from advocacy groups, who contend that by isolating them from society the transition to a new culture will be more difficult.

Critics also point out that South Korea’s strength as a global power will be contingent upon its ability to accept the arrival of more immigrants than it has in the past. In the years of 2000 to 2017, the government authorized refugee status to a mere 3.5 percent of applicants. In 2020, that figure was reduced to 1.1 percent.

The support for Afghan refugees sets a hopeful new precedent for South Korea’s immigrants, but the program’s success remains contingent upon what unfolds in the upcoming months.