Peace in the Middle East: A Fantasy or Possibility?

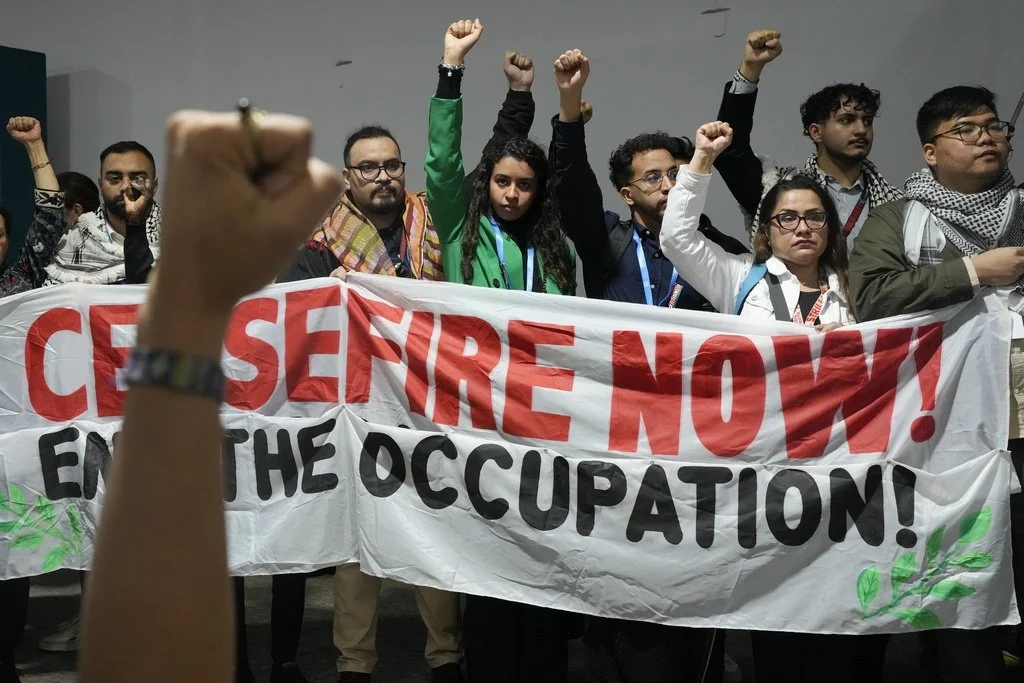

Activists demonstrate for climate justice and a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 11, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

The Middle East has remained unstable for generations, and with the conflict between Israel, Hamas, Hezbollah and recently, Syria’s internal conflicts taking the forefront of the news, the question arises if a ceasefire, or peace in the region, is within reach. Recent talks surrounding ceasefire agreements have flooded Middle East news headlines, with Netanyahu’s minister of strategic affairs, Ron Dermer, discussing the future of Lebanon and possible peace deal during a meeting in Mar-a-Lago before Netanyahu traveled to the White House.

Looking back however, the Middle East has had too many failed negotiations and agreements.

In a personal interview on Oct. 29 with Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, professor at New York University and political scientist (and one of the creators of the selectorate theory, a key theory about governments) – also referred to as BdM – he discussed the Oslo Accords. This was an agreement between Israel and Palestine that has ultimately come to be seen as a failure.

Another failed negotiation is the 50-year-old ceasefire agreement between Israel and Syria which kept a demilitarized buffer zone around Golan Heights. The UN recently said that Israel had done construction and crossed Israeli army vehicles and personnel into and along the “buffer zone” causing violations of the agreement, and risking increased tensions. Furthermore, Israel has unilaterally annexed the Golan Heights since the agreement was put in place.

Recently, Lebanon and Israel have attempted to reach ceasefire deals, with one reaching a conclusion. Even then, it still ultimately hasn’t worked. Israel has demanded freedom to act against the Hezbollah group in Lebanon in the future in response to “future threats.” This has resulted in many being worried that the ceasefire wouldn’t work because the groups don’t agree with each other on this matter, and Israel appears to be continuing to do its own thing.

Another recent Lebanon and Israel talk has been a full implementation of U.N. Security Council resolution 1701, which ended the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah. However, Israel claims that it was never implemented. On the other hand, Hezbollah claims that Israel violated the resolution by having warplanes fly in their airspace.

Qatar has also attempted to act as a ceasefire mediator between Israel and Hamas, briefly reaching a proposal last year. This led to the release of 100 Israeli hostages in exchange for 240 Palestinian prisoners. Qatar has announced that it would pause its role as mediator, as the two sides don’t appear to find common ground to settle on an agreement. Benjamin Netanyahu has ruled out a truce, with intentions to end Hamas completely. Hamas, on the other hand, has demanded a complete end to fighting and withdrawal from Gaza.

Furthermore, Hamas has claimed that they are ready for a serious ceasefire proposal, but both sides have failed to actually follow through on, or even make proposals. In fact, many analysts (such as Hage Ali, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut) believe that Israel is feigning diplomacy; whenever a deal was close, Israel would change its terms, leading to a failed proposal.

Lastly, US attempts to secure commitments from Israel to ensure humanitarian assistance to Gaza have also thus far failed, with no credible commitments taking place.

So what now? In every single one of the ceasefire situations listed, either parties involved believed their preferences were the best and that their deal would be the only successful one.

Here is an important consideration: people have become too polarized about issues and have stopped thinking about them correctly.

We may all have subjective opinions, but a belief is not enough to ignite change. Change requires an understanding of both party’s motivations and then using this understanding to find a compromise.

So is a ceasefire possible? Yes, if the conflict is evaluated differently. BdM explains that every side will believe that they are right, so this should not be assessed based on who is right and wrong. Moreover, it should not be assessed by what is moral and what is not.

Instead, the war in Gaza should be approached from a more practical perspective – one that incorporates interests, beliefs and incentives. The only way to achieve this is by adopting critical analysis and setting opinions aside.

Smoke rises from a building hit in an Israeli airstrike in Dahiyeh, in the southern suburb of Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

BdM provided his insight on the escalations in the Middle East by adopting the selectorate theory: “As I understand how politics works… every leader wants to keep power.” This means that a leader will act on things that their winning coalition believes and needs. This is the group of people that the leader depends on for support and to maintain power.

BdM explained that this is why he would not analyze the situation by who is right or wrong. That is a “matter of opinion and not useful… and every side will believe they are right.” History, as he explained, wasn’t alterable. However, it was useful for understanding people’s preferences and looking for conflict resolutions. One way to do so is to analyze the leader's previous actions and what kept said leader in power.

BdM proposed an alternative way of looking at peace deals. Referencing his 1979 paper discussing the implications of a two-state solution, BdM suggested that Israel declare the West Bank in Gaza as an international sovereign state. This would lead to a two-state solution, and the Israeli government “would have no obligation under international law to do anything for that state.”

This would incentivize the Palestinians to rebuild society. This has been hard to do thus far since the Israelis have made it very difficult, because as BdM explained, “[the Israeli authorities] have not fostered a Palestinian leadership focused on growth and so forth.”

For the Palestinians to achieve independent economic viability, he proposed another simple idea: “Take international tax revenue that would have flowed from tourism and that would have been taxed, put it in an escrow account and dispense that money in proportion to the current population – as a fixed percentage, not to be varied over time.”

He explained that tourist revenue was estimated to be the highest portion of economic revenue for Gaza if a peace deal was to happen. Furthermore, tourist revenue is extremely sensitive to violence, meaning that if “both sides were to police their violence, there would be lots of revenue.” This would result in both parties being incentivized to keep peace. BdM said that “tourist revenue is easily monitored and extremely sensitive to violence, so it’s [a] self-policing mechanism” forcing a credible commitment from both parties.

The idea appears simple and too good to be true. But the reality is, it solves many of the factors that have resulted in the failure of the previous peace deals – no credible commitments and a failure to reach a compromise on both sides for the terms of negotiations. It allows for both parties to pursue their interests. However, this comes at a cost that neither party wants to endure, so they end up sticking to the status quo. Even though the idea appears to not be workable in the status quo, if a military ceasefire is reached, the idea would be one of the first things that could happen – and actually be effective.

There are three important points about BdM’s suggestion. Firstly, it has credible commitments. Second, it’s completely neutral – no side can claim that they are right or wrong in the situation. Lastly, it has an incentive: money. Unlike all previous ceasefire proposals, this one doesn’t rely on parties simply hoping that the groups will commit to the terms of the agreement. Instead, BdM’s suggestion puts incentives in place for them to do so.

All things considered, the issue with merely fixating on what or who is right and wrong has led us to fail the very people we are trying to help. We’re too entrenched in proving to the other side why we are right through Instagram stories of violence, protests, counter protests and chants. But in the middle of all of these acts of heroism – although admirable and effective at documenting the war – we’ve forgotten that we need a solution.

We need one that works towards ending the conflict, and BdM argues that this can only be done by analyzing the preferences of all parties involved and attempting to negotiate to reach these preferences.

BdM’s solution of looking at preferences isn’t biased, it isn’t based on morals and it isn’t based on ideologies – it is simply based on incentives. But yet, it is effective. It can help us reach the military ceasefire we need. It can help us achieve lasting effects once that is reached. But we must look at preferences and reach our negotiations through them.

It’s the only hope the Middle East has.