The Central Bank’s Balancing Act in Australia: Managing Inflation without Crashing the Housing Market

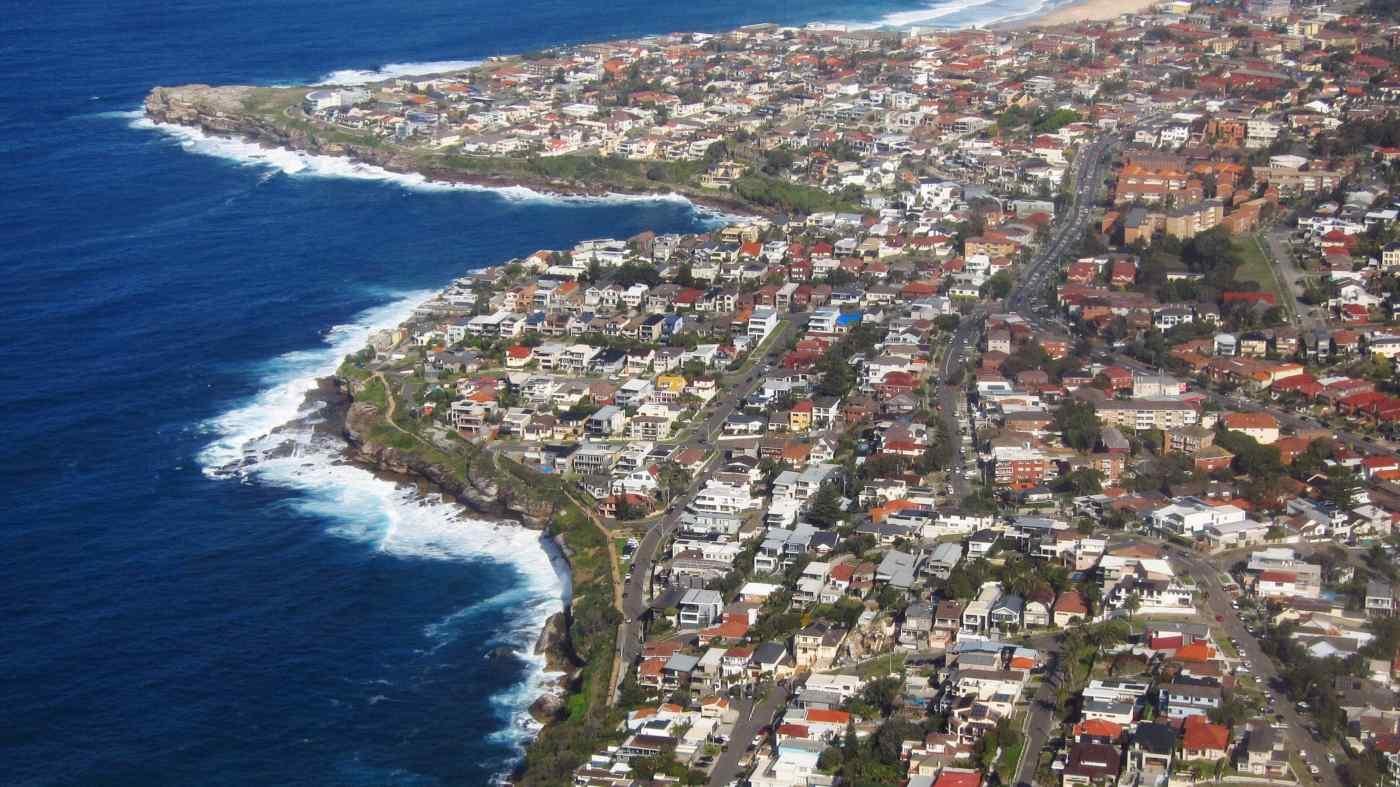

Australia's AU$9.4 trillion housing stock is worth 4x its GDP. Source: Nikkei Asia Review

In early December, The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) lifted interest rates for the eighth consecutive month, taking its benchmark to 3.1%.

Philip Lowe, Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, has repeatedly talked about his aim to achieve a "soft landing" for the economy in its battle against inflation.

A soft landing is a cyclical slowdown in economic growth, avoiding a recession. In this instance, the RBA is attempting to raise interest rates just enough to stop the Australian economy from overheating, without causing a severe downturn. Australia’s pivotal housing sector seems to be the biggest obstacle for the RBA to achieve this “soft landing”.

This is because Australia's AU$9.4 trillion housing stock is worth more than four times the size of its gross domestic product. The Australian housing market also holds nearly AU$2 trillion ($1.35 trillion) of debt and has the dual issue of being an investment as much as an accommodation for the people there.

More importantly, it also shows how risky continuous interest rate hikes can be. Economists suspect that a recession is inevitable if home prices plummet by more than the expected 20% from their peak earlier this year.

Australia’s inflation rate forecast shows the need to combat a long-term inflation problem. Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Australian home prices fell for a seventh straight month in November – a drag on household wealth that would curb consumer confidence and consumption over the months ahead.

Maree Kilroy, a Senior Economist at BIS Oxford Economics, claims that interest rates are the key factor underpinning the property market downturn. According to her, it is “a credit availability issue that is driving this downturn, unlike a rise in unemployment or an oversupply in the market.” In other words, as long as interest rates keep rising, property prices will continue falling.

While the problem of long-term inflation must be addressed, the RBA should watch property prices as intently due to the influence they have over the other moving parts of the economy.

On the one hand, aggressive interest rate rises will help curb unsustainable rises in inflation. On the other hand, a big downturn in house prices could negatively, contracting consumption. The Australian household sector is already burdened by some of the highest debt levels in the world with higher borrowing costs, and more expensive mortgages may cause people to further retreat from the housing market.

As of now, Australia’s home price correction has been orderly, and loan arrears are still low. There is no talk of recession or a dramatic crash in the housing market. But the RBA must continuously monitor their balancing act between combating inflation and safeguarding economic growth.

If they can get it right, Australia might just have achieved a spending slowdown without engineering a recession in their AU$2.2 trillion economy. It will be no easy feat.