Demise of Russian Grain Deal Threatens Middle East, Africa

Grain is loaded into shipping containers during harvesting in Ukraine. Photo: Reuters via Al-Jazeera.

Earlier this week, a landmark deal to allow for the export of agricultural products from Ukrainian ports collapsed, magnifying a crisis of food instability in the Middle East and Africa that predated Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (and subsequent mining of the Black Sea) and has only expanded since then.

Dmitry Peskov, the spokesperson for the Kremlin, threatened on Oct. 31 that proceeding with the Black Sea grain deal "is hardly feasible," "much more risky" and "dangerous."

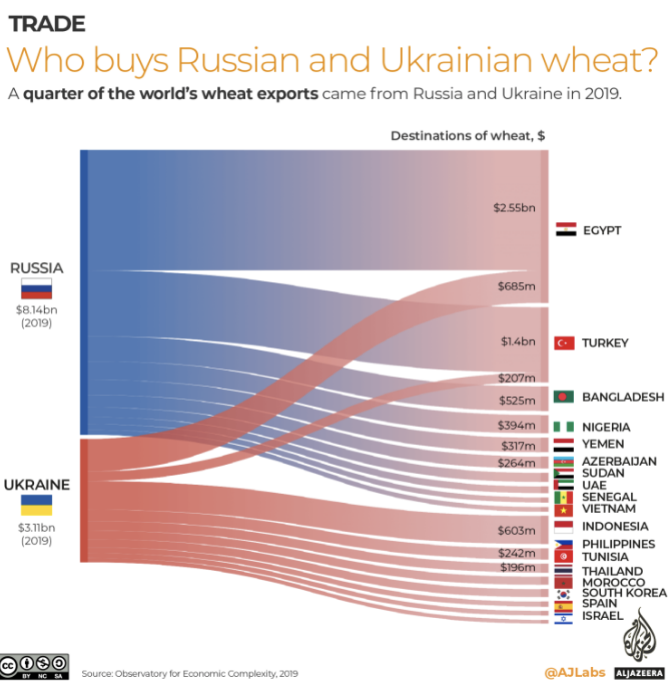

As I wrote in April, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year threw global supply chains of grain (and oil) into chaos. While Russia and Ukraine are by no means the largest producers of wheat or cereal grains (the United States far outstrips them both), they long filled a niche of supplying less expensive wheat to the Middle East, Africa, and, to a lesser extent, Europe.

Although sanctions on Russia instituted by the United States, EU, and allies do not apply to grain, other essential foodstuffs, or fertilizer, they have generally complicated the logistics of Russian businesses. Grain production and exports from Ukraine have fallen drastically as farmers went to war, evacuations prevented plantings and harvests from proceeding on schedule, and missile attacks burned fields.

A sustained decline in agricultural output is a common effect of war. In many war-torn countries, climate change and conflict combined to wipe out harvests; resulting economic decline compounded the process over several years until large swaths of the conflict zones became dependent on humanitarian aid for food.

Before the war, Ukraine exported around 50 million tons of wheat each year; the war created a backlog of 20 million tons by midsummer. The World Food Programme estimated that Ukrainian exports of grain fed 400 million people in 2021, many in the Middle East and North Africa.

As surviving grain rotted in Ukrainian ports (especially in Odessa) with no safe passage out of the country, the United Nations brokered an agreement between Russia and Ukraine that would guarantee civilian ships carrying food supplies a route through the Black Sea to global markets.

The "Black Sea Grain Initiative" was hammered out in July, with the first ships leaving Odessa on August 1. Many were Lebanese-flagged and traveled first to Istanbul before continuing elsewhere in the Middle East or Asia. Inspections took place in Turkish waters.

The grain shipments faced difficulties from the start; the first ship bound for Lebanon, the Razoni, meant to arrive on Aug. 4, was delayed several days. On Aug. 7, four ships left bound for China, Iran, Italy, and Turkey, carrying a total of 160,000 metric tons of corn and sunflower oil. On Aug. 16, the first shipment of grain to leave Ukraine by sea set off for the Horn of Africa with 23,000 metric tons of grain onboard. It was followed soon after by a ship with another 7,000 metric tons of Ukrainian grain on board, bound for Djibouti, the de facto port for drought- and famine-stricken regions of Somalia and Ethiopia.

A chart displaying the distribution of Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports to Asia and Africa. Photo: Al-Jazeera Labs

On Oct. 21, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky publicly accused Russia of “delaying” 150 ships from Ukrainian ports, leading to a reduction of three million tons of agricultural exports. The deal was originally scheduled to expire on Nov. 30 but was already on shaky ground prior to a growing Ukrainian offensive.

Then, on Oct. 29, in response to a Ukrainian drone attack in the Crimea, the Kremlin released a statement saying that Russia will "no longer guarantee the safety of civilian dry cargo ships participating in the Black Sea Grain Initiative and will suspend its implementation from today for an indefinite period."

Turkey, which has made a concerted effort since the beginning of Russia's war in Ukraine to cast itself as an international power and unbiased mediator, continues to maintain diplomatic discussions with Russia on the grain deal. Within hours of Russia's announcement, the Turkish Defense Ministry released a statement saying that the Turkish Defense Minister, Hulusi Akar, planned to speak to his Russian counterpart Sergei Shoigu discuss the agreement. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan also announced his intention to aid the grain deal, saying, "Although Russia is hesitant in this regard because it could not benefit in the same way [as Ukraine did], we will decisively continue our efforts to serve humanity."

Jeune Afrique, a popular news site in Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, headlined its homepage on Oct. 31 with “Ukrainian grain: what awaits Africa after a new crisis?” Murithi Mutiga, the Africa program director for the International Crisis Group, told the New York Times that the end of the deal "[could] spell considerable trouble not only for the neediest countries on the continent, but also even for the bigger countries where the cost of living has become a potent political issue.”