Has the Fed Pulled Off a Soft Landing?

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell speaks during a news conference at the Federal Reserve in Washington, Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

For the past few months, the US economy has been poised in a precarious position: core inflation stubbornly persistent at a smidge above 3% YoY (above the Fed’s target of 2%), job market showing signs of weakness, and unemployment jumping to 4.3% in July (a three year high).

Having brought down inflation from 8% in 2022, the Fed has sought to pull off a “soft landing” – cool inflation without triggering a recession, for the last two years. On Sept. 18, with pressure from a weakening labor market, the Fed made a 50 bps rate cut to stimulate the faltering economy, believing that inflation would cool as the lowered interest rates filter through the economy. However, Fed Governor Michelle Bowman, the sole dissenter to the 50 bps cut, expressed concern that such a large reduction could risk fueling inflation instead. In this light, the 50 bps cut appears to have been motivated more by the fear of recession than by confidence that the Fed has fully tamed inflation.

On Friday, the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) announced that the US economy added 254,000 jobs in September, far outperforming economists’ forecasts at around 140,000. The job gains have been widespread, spanning across industries, including F&B (69,000), healthcare (45,000), and construction (25,000). Diane Swonk, the chief economist at KPMG, noted that the blowout jobs report indicates “the labor market is apparently not cooling as rapidly as we thought”, raising the question: In deciding to cut interest rates by 50 bps, did the Fed panic? David Royal, CFO at Thrivent, believes that, “it is doubtful” the Fed would have cut by so much “if it had known this report would be so strong”, especially given ongoing concerns about reigniting inflation.

In any case, a resilient labor market nearly rules out the chance of another 50 bps cut. Assuming there are no unpleasant surprises, the Fed will likely revert to the standard 25 bps cuts from now on, increasing the chance of sticking a soft landing. As inflation inches closer to the Fed’s target (the PCE, the Fed’s preferred gauge for inflation, dropped to 2.2% YoY in August), the economy has continued to remain strong despite recessionary fears. However, even if Fed officials unanimously agree on the pace of cuts (25 bps at a time), there is still significant disagreement about the long term direction of interest rates, with officials’ projections ranging anywhere from 2.375% to 3.75%.

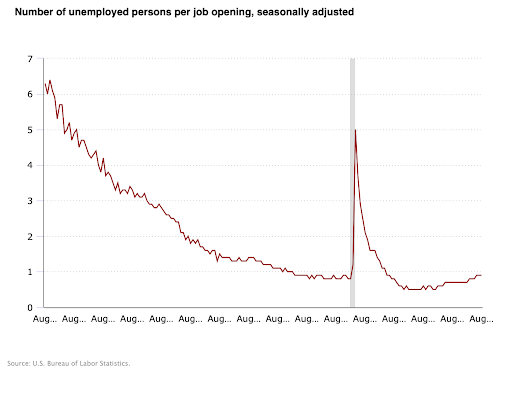

As for the broader economic implications of a growing labor market, while the data is undoubtedly in favor of the economy, it nevertheless raises concerns about a potential labor shortage. For example, job vacancies rose to 8mn in August (from 7.7mn in July), exceeding the number of unemployed workers.

Number of unemployed persons per job opening, seasonally adjusted. (US Bureau of Labour Statistics)

This increase is partially due to the labor force participation rate, which remains below pre-pandemic levels. In addition to the labor shortage, the labor market has also become increasingly rigid, with the number of Americans quitting their jobs hitting a record low since August 2020. Moreover, even as the layoff rate remains at a historic low of 1%, the hiring rate has fallen to its lowest level since October 2013. Usually, a higher hiring rate - despite potential layoffs- is better for the economy, as it allows workers to take up jobs they may be more suited to, thereby increasing labor productivity. Hence, a “no-hire, no-fire labor market” suggests that employers have an ambivalent outlook towards the economy- they are not pessimistic to the point of laying off workers, yet not confident enough to increase hiring due to concerns about an economic slowdown.