Inflation Spreads to North Africa as War in Ukraine Spikes Grain, Fertilizer Prices

A wheatfield in Zakarpattia, Ukraine. The country is one of the primary sources for agricultural products sent as humanitarian aid to the Middle East & North Africa. Photo: Serhii Hudak- Ukrinform/Future Publishing

More than a month after Russia launched a further invasion against Ukraine, the effects of the war are still reverberating across the world. In light of Russia’s aggression and ensuing foreign sanctions, North Africa, long a recipient of Russia’s foreign investment, has seen its imports and its investments put into jeopardy. While the Soviet Union once maintained significant social and economic ties throughout Africa, supporting communist governments or insurgencies at various times in Angola, Ethiopia, and South Africa, as well as communist political movements in most North African nations, Russia’s role on the continent shrunk greatly after the collapse of the USSR. In the 1990s and beyond, Ukraine, Belarus, and particularly Russia struggled with economic downturns in the chaos of privatization and a transition to a free market.

Upon these transitions, some of the only reliable exports from the former Soviet Union to reach North Africa (aside from weapons) were agricultural products. Additionally, many other crops grown in North Africa and elsewhere rely on fertilizers such as potash, of which the majority of the world’s supply is mined between Russia and Belarus. While food products are not traditionally subject to most sanctions, potash is. As Russian troops destroy Ukrainian cities and impede the harvest and export of wheat, and foreign sanctions (from the US, EU and elsewhere) impede business transactions in Russia and its allies in Lukashenko’s Belarus, the entire supply chain for essential food products in North Africa may be cast into chaos.

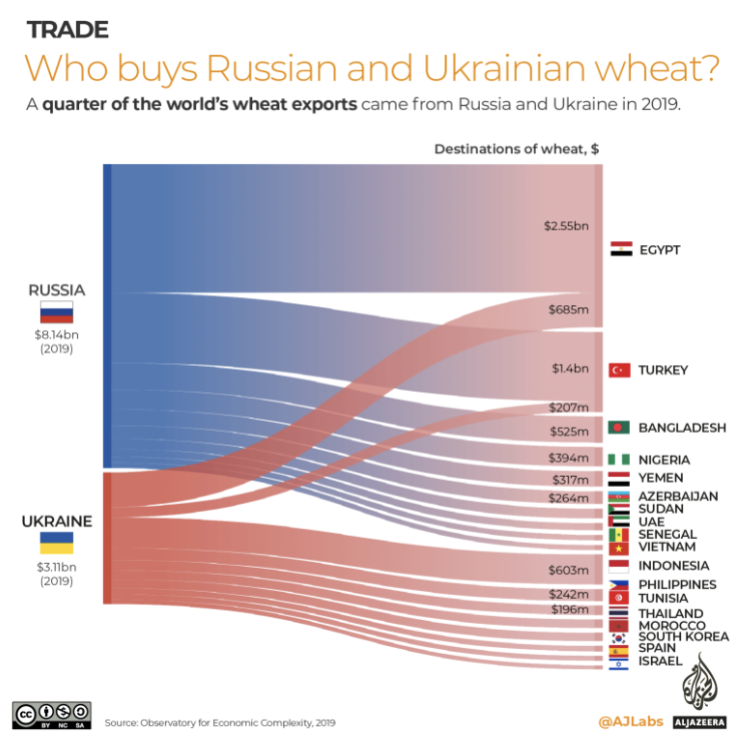

Ukraine, long known as the breadbasket of Europe, supplied 7.4 percent of the world’s grain in 2019, compared to Russia with 18 percent (and the United States’ seven percent). About 50 percent of Ukraine’s wheat exports went to the Middle East and North Africa in 2020. In the same year, African countries imported $2.9 billion in agricultural projects from Ukraine. Egypt, which is Russia’s top trading partner in Africa, gets 85 percent of its grain from Ukraine and Russia. Wheat imports account for about 90 percent of Africa’s $4 billion agricultural trade with Russia and almost half of its $4.5 billion trade with Ukraine. Wheat prices have already increased rapidly in recent years in the Middle East and North Africa as a result of regional droughts and the COVID-19 pandemic – the IMF found a nearly 80 percent price increase between April 2020 and December 2021. In Egypt, the price of bread at non-subsidized bakeries rose more than 50 percent in the four months before Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine.

The near total drop in Ukrainian wheat exports is expected to inflate the prices of essential goods even further. Tunisia announced in the second week of the war that it would begin looking for new sources of wheat and food reserves. According to David Wright, the chief operating officer for charity Save the Children International, 86 percent of Sudan's wheat imports are at risk after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, because they are sourced from Russia or Ukraine. Similar numbers are applicable to humanitarian aid in food-insecure regions of Ethiopia.The situation prompted the African Development Bank to announce a $1 billion fund to promote resilient farming in Africa (eventually assisting about 40 million farmers), in March.

A chart displaying the distribution of Russian and Ukrainian wheat exports to Asia and Africa. Photo: Al-Jazeera Labs

Some African nations, including Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria, have made vocal declarations of support for the sovereignty of Ukraine and joined in on sanctions against Russia. More authoritarian nations have sided with Russia, however. South Africa, the continent’s third largest economy, has taken an explicitly neutral stance. This may be, in part, because of growing Russian investment in Africa in recent decades, as well as the military pressure Russia and its allies have exploited in various proxy wars in the region.

Russia is not as big of a player as China or the United States from a macroeconomic standpoint – it has a far weaker domestic economy, even before the most recent round of sanctions – but it has found beneficial trading arrangements with countries with which it can find common political cause. These countries have backed up Russia, and a coalition with them (as well as China and other non-aligned or anti-democratic countries) may keep the Russian economy stable, thus prolonging the war in Ukraine. What is certain, however, is that until the war is over (and even after, due to the destruction of agricultural land), many North African nations will need to pivot to new sources of agricultural exports, shore up local reserves, or face increased food insecurity, and face all of the political and economic challenges that result.